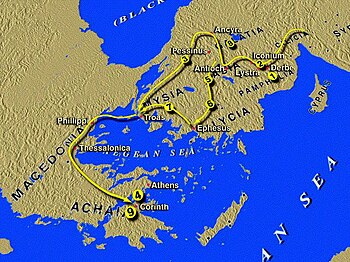

| English: Map of the Letters of Galatia (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

In

the first entry in the Bible Junkies Online Commentary on Galatians, I

discussed introductory matters concerning the founding of the churches to the

Galatians, the situation when Paul wrote to them, when the letter might have

been written and the type of letters which Paul wrote, based on the common

Greco-Roman letters of his day. In

the second post, I considered the basic content and breakdown of a Pauline

letter. I noted the major sections of the formal letter structure and, in the

context of each section, outlined the theological and ethical (as well as

other) concerns of Paul, including some Greek words which will be examined more

fully as we continue with the commentary. In

the third entry, I looked at the salutation, which is long for Paul’s

corpus (only Romans 1:1-7 is longer) and briefly commented on the lack of a

Thanksgiving, the only letter of Paul’s which does not have one. The

fourth entry discussed the opening of the body of the letter, a significant

part of the letter especially in light of the absence of a Thanksgiving. In

the fifth entry, I examined the beginning of the opening of the body of the

letter, in which Paul describes his background in Judaism and I placed this in the

context of Judaism in the Hellenistic period. In the

sixth post in the online commentary, I continued to look at Paul’s

biographical sketch of his life, this concerning his earliest life as a

Christian. In

the seventh post, I examined what Paul says about his subsequent visit to

Jerusalem to see the apostles and the Church in Jerusalem.

In the eighth entry, Paul confronts Cephas about his hypocrisy in

Antioch.

The

ninth blog post started to examine the theological argument in one of

Paul’s most important and complex theological letters. In

the tenth entry, Paul makes an emotional appeal to the Galatians based on

their past religious experiences and their relationship with Paul. In

the eleventh chapter in the series, Paul began to examine Abraham in light

of his faith. The

twelfth blog post continued Paul’s examination of Abraham, but also claims

that Christ “redeemed” his followers from the “curse” of the Law. In

the thirteenth study in the Galatians online commentary, we looked at Paul’s

claim that God’s promises were to Abraham and his “offspring,” with a twist on

the meaning of “offspring.” The

fourteenth entry examined Paul’s question, in light of his claims about the

law, as to why God gave the law. The

fifteenth chapter in this commentary examines the function of the law,

while the

sixteenth post studied how the members of the Church are heirs to the

promise.

In

the seventeenth entry, I observed what it means to be an heir in Paul’s

theological scenario. And in the

eighteenth installment, Paul transitions back to his relationship with the

Galatians, but before he concentrates on this in full, he returns to the issue

of the stoicheia, commonly known as

the four cosmic powers, earth, air,

water and fire. In the nineteenth blog post, Paul relies on his personal relations with

the Galatians to draw them to his point of view. In the twentieth entry, Paul

speaks of an allegory of Hagar and Sarah. The twenty-first chapter in the

series, found below, finds Paul speaking against circumcision.

4. Paul’s Letter to the Galatians

d) Body of the Letter (1:13-6:10):

iv) Theological Teaching (2:15-5:12): Against

Circumcision (5:2-12).

2 Listen! I, Paul, am

telling you that if you let yourselves be circumcised, Christ will be of no

benefit to you. 3 Once again I testify to every man who lets himself be

circumcised that he is obliged to obey the entire law. 4 You who want to be

justified by the law have cut yourselves off from Christ; you have fallen away

from grace. 5 For through the Spirit, by faith, we eagerly wait for the hope of

righteousness. 6 For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision

counts for anything; the only thing that counts is faith working through

love. 7 You were running well; who prevented you from obeying the truth? 8 Such

persuasion does not come from the one who calls you. 9 A little yeast leavens

the whole batch of dough. 10 I am confident about you in the Lord that you will

not think otherwise. But whoever it is that is confusing you will pay the

penalty. 11 But my friends, why am I still being persecuted if I

am still preaching circumcision? In that case the offense of the cross has been

removed. 12 I wish those who unsettle you would castrate themselves! (NRSV)

Paul changes to a more personal tone when he begins to speak against circumcision,

connecting his theological claims more directly to his relationships with the

Galatians. Paul is characteristically blunt, saying that “if you let yourselves

be circumcised, Christ will be of no benefit to you” (Galatians 5:2). Paul claims

that “Christ will be of no benefit” if they are circumcised, not because

circumcision is of itself more than an indifferent (adiaphoron, see Galatians 5:6 below) from Paul’s point of view, or

negates the saving work of Christ in bringing the Galatians into the covenantal

family, but because the Galatians are insisting that circumcision is essential

to salvation for the men of the community, perhaps (especially?) including

newborn infant boys. If the claim is that salvation in Christ for these male

members of the community is dependent upon circumcision, then this would

account, I think, for Paul’s hostile tone: nothing need to be added on to the

work Christ has accomplished.

Paul ups the ante, in a sense, stressing that the implications for the

choice of circumcision transcend the simple rite itself: “Once again I testify

to every man who lets himself be circumcised that he is obliged to obey the

entire law” (Galatians 5:3). The better

way to translate “obliged to obey the entire law” is obliged to “do the whole

law” (5:3: holon ton nomon poiēsai).

Paul is consistent in using the verb “to do” when he speaks of the law apart

from Christ and its demands, which indicates that every particular element of

the law must be observed. Recall that Paul has already argued in 3:10-14

that this cannot be done, but even more he says to those who desire

circumcision: “you who want to be justified by the law have cut yourselves off

from Christ; you have fallen away from grace” (Galatians 5:4). Paul sees circumcision

as a fundamental rejection of the

righteousness and grace – key theological terms from earlier in the letter

- which come through following Christ. The verb used in the phrase “have cut

yourselves off from Christ,” seems to be a play on the physical cutting

involved in circumcision and perhaps it is. The basic rendering of katargeō is usually “to make something powerless, or ineffective,” but

it is possible that the sense of “removed yourself from Christ” is in play

here, which would be a corollary to the removal of the foreskin. “Cut yourself

off” simply makes the image clearer.

Paul then returns to a basic statement of the hope in Christ, declaring

that “through the Spirit, by faith, we eagerly wait for the hope of

righteousness. For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision

counts for anything; the only thing that counts is faith working through love”

(Galatians 5:5-6). This what I meant

above by saying that circumcision is an adiaphoron,

or “indifferent,” as Stoic philosophers claimed of those things which were

morally insignificant. Paul does not use the term here, but this is the

implication of his stance. Not circumcision or akrobystia (literally “foreskin” or figuratively “uncircumcision”)

matter at all, but only “faith working (energoumenē)

through love (di’ agapēs).” Paul manages

to pack into this verse two of his central theological concepts: faith and love; but what is interesting

is how he uses the verb “work” not to speak of the Law of Moses, but of how

faith is enacted through love. Usually, as

seen in entry 10, “work” or “works” has a negative sense, but not when

connected to faith and love, the work by which Paul understands entry into the

covenant through Christ.

At this point, Paul turns to a general accusation against the Galatians

and the interlopers (about whom I speak in entry

4 and elsewhere)

whom Paul believes must have led them down this errant path. He writes, “You

were running well; who prevented you from obeying the truth? Such persuasion

does not come from the one who calls you. A little yeast leavens the whole

batch of dough” (Galatians 5:7-9). In some ways, though, Paul is not blaming

the Galatians, but treating

them indeed like children who are not capable of making their own choice. Paul is giving the Galatians an out, allowing

them to blame the interlopers who came into the community for their errors, which

also allows them an excuse for their own choices and a way back into Paul’s

good graces. The proverb, “A little yeast leavens the whole batch of dough,” is

also found in 1 Corinthians 5:6 and here must indicate that if they allow the

interlopers a foot in the door, they will take over the whole house and

community.

Finally, Paul turns to encouragement, and disdain of the interlopers, writing

that “I am confident about you in the Lord that you will not think otherwise.

But whoever it is that is confusing you will pay the penalty. But my friends,

why am I still being persecuted if I am still preaching circumcision? In that

case the offense of the cross has been removed. I wish those who unsettle you

would castrate themselves!” (Galatians 5:10-12). Paul hopes that the Galatians

will heed his advice, especially about the attempt of the interlopers to win

over the whole community, and his confidence must be that they will see Paul’s

point of view and return to the Gospel he preaches. He also wants them to “pay

the penalty,” whatever that might be. At least a part of the interlopers’ entry

into the community must have been their claim that Paul himself was divided

about circumcision – “why am I still being persecuted if I am still preaching

circumcision?” – but he assures them that he would not be persecuted in his

ministry if he still preached circumcision. At the end, Paul breaks out perhaps

his most sarcastic comment –saltiest and most sarcastic? – when he says that he

hopes those “who unsettle you would castrate themselves.” Ouch, at every level!

This indicates Paul at the end of his rhetorical tether, though I think he has

chosen this phrase rationally (obviously also because of the knife and genital

imagery) to shock the Galatians. Having reached this angry crescendo, though, to

where will Paul turn next? He must feel he has done his job successfully, for

he will next write on what it means to live in the freedom of Christ, which

comes from faith working through love, not the works of the law such as

circumcision.

Next entry, Paul speaks of the ethical implications of freedom in Christ

John W. Martens

I invite you to follow

me on Twitter @Biblejunkies

I encourage you to

“Like” Biblejunkies on Facebook.

This entry is cross-posted at America Magazine The Good Word