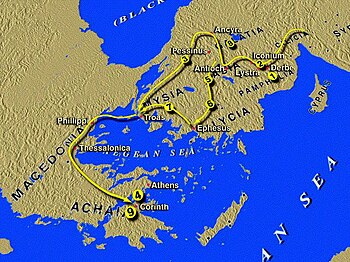

| English: Map of the Letters of Galatia (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

In

the first entry in the Bible Junkies Online Commentary on Galatians, I

discussed introductory matters concerning the founding of the churches to the

Galatians, the situation when Paul wrote to them, when the letter might have

been written and the type of letters which Paul wrote, based on the common

Greco-Roman letters of his day. In

the second post, I considered the basic content and breakdown of a Pauline

letter. I noted the major sections of the formal letter structure and, in the

context of each section, outlined the theological and ethical (as well as

other) concerns of Paul, including some Greek words which will be examined more

fully as we continue with the commentary. In

the third entry, I looked at the salutation, which is long for Paul’s

corpus (only Romans 1:1-7 is longer) and briefly commented on the lack of a

Thanksgiving, the only letter of Paul’s which does not have one. The

fourth entry discussed the opening of the body of the letter, a significant

part of the letter especially in light of the absence of a Thanksgiving. In

the fifth entry, I examined the beginning of the opening of the body of the

letter, in which Paul describes his background in Judaism and I placed this in

the context of Judaism in the Hellenistic period. In this, the sixth post in

the online commentary, I continue to look at Paul’s biographical sketch of his

life, this concerning his earliest life as a Christian.

4. Paul’s Letter to the Galatians

d) Body of the Letter (1:13-6:10):

ii) Paul's Background in the Church 1 (1:18-24):

18 Then after

three years I did go up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas and stayed with him

fifteen days; 19 but I did not see any other apostle except

James the Lord’s brother. 20 In what I am writing to you,

before God, I do not lie! 21 Then I went into the regions of

Syria and Cilicia, 22 and I was still unknown by sight to the

churches of Judea that are in Christ; 23 they only heard it

said, “The one who formerly was persecuting us is now proclaiming the faith he

once tried to destroy.” 24 And they glorified God because of

me. (NRSV)

Paul recalls his

initial visit with the Apostles in Jerusalem three years after his conversion,[1]

which includes he says only Peter (Cephas) and James the Lord’s brother. (1:18-24).

He then returned to Syria and Cilicia (his hometown of Tarsus was in Cilicia),

but his reputation had now spread to the churches in Judea.

The focus of this

section, as

noted last entry, is that Paul was not dependent upon any human being as

the source of his Gospel, but instead was guided by the “revelation” of Jesus

Christ. Here he states that he met Cephas only after three years. Cephas is

Aramaic for “rock” and though the identity of Cephas has been disputed, it

seems clear that it refers to Peter, which is Greek for “rock.” Why Paul uses

Cephas instead of Peter in a Greek letter is intriguing, but difficult to

answer. He might simply prefer Peter’s name in the mother tongue (see note

below). What Paul desires from Peter is also left vague.

Paul writes that he “I

did go up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas and stayed with him fifteen days”

(1:18). What sort of “visit” was this? The verb used here, historêsai, can have the sense of gaining knowledge through face to

face encounter, so visit might work, but it also has the meaning of enquiring,

learning and examining a thing or a person. Given the context in this letter,

of Paul’s self-sufficiency in the Gospel, and then his acknowledgement that he

did “visit” Peter for fifteen days, I think it is best to understand Paul’s

visit as having the purpose of enquiring about Jesus’ earthly ministry and

Peter’s reminiscences about that ministry.[2]

Paul’s visit had as its purposes research

and personal contact.

Paul then defends

himself, it seems to me, against unknown interlocutors and charges – made by the

Galatians? The interlopers who were unsettling the Galatians? – that he saw no

other apostle “except James the Lord’s brother” (1:19). There is actually some

question as to whether this phrase means to exclude James from the apostles or

to include him among the apostles. Literally the Greek phrase which is

translated as “except” is “if not” (ei mê).

This could be adversative and mean “but”: “I did not see any other apostle, but (I

did see) James the Lord’s brother.” Or, it could mean “except”: “I did not

see any other apostle except James

the Lord’s brother.” I prefer “except,” even though James, the Lord’s brother

was not considered one of the twelve apostles. It seems clear, however, that “apostles”

was a broader category in the early Church than just the twelve, as we can see

in Romans 16:7, in which Andronicus and Junia are noted as apostles.

Who is this James?

It is not one of the twelve apostles, see

my outline of each James in the NT, but is clearly a relation of Jesus, the

one who was considered the first bishop of the Jerusalem church. We see this

James guiding the Church in Jerusalem not only in Galatians 2:9, 12, but in

Acts 15: 13 (and most likely Acts 12:17 and 21:18). Catholics, of course, deny

that Jesus had any full brothers or sisters and so would understand “brother”

in the broader sense of “relation” or “kinsman” or “cousin” (as for instance

Fitzmyer, NJBC, 783). Paul’s meeting

with James would be a recognition of James’ standing within the Jerusalem

church.

Paul then states, “In

what I am writing to you, before God, I do not lie!” (1:20). It is the vociferous

denial here which leads me to say, as above, that Paul is mounting a defense

against some charges thrown his way. What charges? That he has had more contact

with Jerusalem then he is letting on? That he is more dependent upon other

apostles than he wants them to know? Is this an attack on his apostleship? Paul’s

apostleship depends upon a religious experience, not an earthly ministry in

which he followed Jesus, so perhaps the charge leveled against him is that his

conversion cannot be trusted and he is only a follower of the apostles in Jerusalem not a leader, so

what kind of authority does he have? On the other hand, as we shall see, Paul

will want to align himself with the authority of the Jerusalem Church to

demonstrate that they accept him and do not reject his Gospel. It is a tight

wire he walks: I am an independent authority, but the apostles, who I did not

know and was not dependent upon, approve of and support my message.

Paul then summarizes

his next travels following his first Jerusalem visit with Peter and James,

three years after his conversion, saying he “went into the regions of Syria and

Cilicia” (1:21), which would include his home city of Tarsus and the major

early Christian center of Antioch. In Acts 13 and 14, Paul’s missionary

activities are outlined in this region and I suspect that this correlates with

the activity surveyed briefly in Galatians 1:21 but that cannot be certain.

Still, Paul was “still unknown by sight to the churches of Judea that are in

Christ; they only heard it said, “The one who formerly was persecuting us is

now proclaiming the faith he once tried to destroy.” And they glorified God

because of me” (1:22-24). Paul ends this section by again asserting his

dependent independence, focusing on his unique missionary activity, without the

support of the churches in Judea, including Jerusalem, but with their tacit support

since “they glorified God because of me.” What they knew of Paul was simply

that the persecutor had become a missionary for the Church.

Next entry, Paul travels to Jerusalem fourteen years later to

meet the Apostles.

John W. Martens

I

invite you to follow me on Twitter @Biblejunkies

I

encourage you to “Like” Biblejunkies on Facebook.

This entry is cross-posted at

America Magazine The Good Word

[1]

This period of three years could be reckoned two ways: a) three years after

Paul’s conversion; b) three years after his journey to Arabia and return to Damascus,

with the conversion, of course, preceding both the journey and return. Since we

do not know how long this sojourn in Arabia was, I think it best just to speak

of this as “three years after his conversion.”

[2]

As an aside, if they spoke in Aramaic during this fifteen day visit, could this

be the source of Paul’s use of Cephas and not Peter? That is, this is the name

and linguistic context for how Paul came to know Peter.