http://americamagazine.org/content/good-word/fr-donal-mcilraith%E2%80%99s-everybody%E2%80%99s-apocalypse

|

|

| English: The Navarra Beatus (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

I had heard many rumors about Columban Fr. Donal McIlraith’s

book on the Revelation of John, Everybody’s

Apocalypse: A Reflection Guide

(published 1995) long before I had seen it or laid hands on it.

Other Catholic biblical scholars, most of whom had studied at the

Gregorian University in Rome or at the Pontifical Biblical Institute, including

Fr. Scott Carl of the St. Paul Seminary, knew of the little book and spoke

highly of it. There was one little problem with the book: it was difficult to

find or purchase. In this day of easy access to books – when I see a novel I

want on amazon.com, with one click it is on my Kindle – this was that rarity, a

hard to find book!

On November 10, 2013, however, I found an e-mail in my inbox

from my retired colleague Fr. David Smith, a New Testament scholar himself, saying

that Fr. Donal would be celebrating Mass that night in Minneapolis. The problem

was that Nov. 10 is my birthday and I could not make it to the Mass due to

other plans. I e-mailed David and asked him to ask Fr. Donal how to acquire a

copy of his book. I thought nothing more about it – I did not hear back one way

or another – but about two weeks later, I looked in my office mailbox and there

was a copy of Everybody’s Apocalypse:

A Reflection Guide, with a short note

from Fr. Donal.

I was excited, but did not have time to read it until now.

Here is what I can tell you about the book and its origin. Fr. Donal teaches in

Suva, Fiji at the Pacific Regional Seminary and also at Pacific Regional

College and Corpus Christi Training College. He once taught at my university,

the University of St. Thomas (five years in the 70s-80s), which is why he was

in town in November celebrating Mass and visiting old friends, but has been in

Fiji since 1989. There are benefits to

being in Fiji, even if book distribution is not one of them, since Fr. Donal

told me it was 93 F (32/33 C) on the weekend, whereas it is -11 F (-24C) today

in St. Paul. (I think if John had been exiled in Minnesota and not Patmos, hell

would be frozen lakes and not lakes of fire.)

The book is only 124 pages, which includes five appendices

and a short bibliography. The content of the book initially appeared as articles

for the Fijian Catholic newspaper Contact

and then later was published in the Tongan Catholic newspaper Taumu’a Leilei. The book is a

compilation of these articles and is published by the Pacific Regional Seminary

(ISBN: 982-342-001-7). Fr. Donal studied the apocalypse under Fr. Ugo Vanni, SJ

at the Gregorian University and at the Pontifical Biblical Institute. His

doctoral thesis, supervised by Vanni,

was on the Covenantal/ Nuptial reality in the Apocalypse (which itself is being

revised as a book).

The book is published

in Fiji and makes its way to the US and elsewhere every now and then, but it is

not available broadly. Other Catholic biblical scholars have touted the book to

publishers, but one major publisher felt it was too technical and would not

sell. But if this little book is too technical, it is hard to see what book on

the apocalypse could be published for a broad audience and what a “less

technical” book on the apocalypse would look like. This book has no footnotes

and carries its deep learning lightly, expressing insights into the apocalyptic

genre, the Greek language, and 1st century Roman life without

bogging readers down in minutiae of scholarship.

The reality is that

apocalyptic language is complex, mysterious, confusing and difficult. As Fr.

Donal writes, “it is good to be puzzled by the symbols. They are supposed to be

puzzling. They are supposed to make us stop and think – and pray” (35). A bit

later he picks up this theme, saying, “the task of understanding each symbol

and seeing its relationship to the entirety of the symbols of this book is a

difficult task to which the Church of each age is called. This discernment

process should be carried out at various levels. Such a process would then

assist the Church to evaluate the age in which it lives in the light of the

Gospel” (37). If this literate guide, or others like it, are not available to people

in the pews, they will find their information elsewhere, because people are

attracted to John’s Revelation, and many untrustworthy sources are readily

available on the internet.

Fr. Donal’s book,

written for regional newspapers, is not overly technical, but it is careful and

precise, in an attempt as he says “to make this puzzling part of the Scriptures

more accessible to people as requested by Vatican II (Dei verbum 5)” (v). The book is accessible for readers who want to

understand the Revelation of John from an expert because it covers all of the

bases an expert must cover but does it without all of the scholarly apparatus

which can bog non-specialists down. It has, appropriately, seven chapters, but each

chapter is divided into numerous subsections based on the text of Revelation.

So, for instance, Chapter One, covering the Vision of Christ in 1:4-20, has

five subsections covering six pages. Each subsection has the appropriate biblical

text and then comment, with two or three questions at the end for further

reflection.

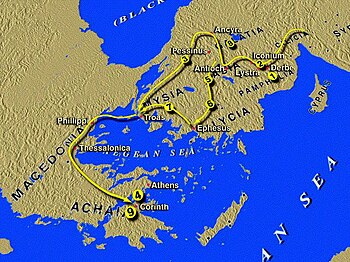

The text is also

accompanied by (black and white) reproductions of illustrations from the Abbott

Beatus’ (d. 798 A.D.) commentary on the Apocalypse. (Fr. Donal told me that “a Fijian

translation is almost ready for printing and that will be in full color.”)

There are also 13 “information boxes” spread throughout the short book, which

deal with topics such as authorship, symbols, early Roman emperors, etc. This

is a terrific way to deal with essential historical data without bogging the

text down. As I said earlier, the book also has five appendices which cover symbols

in more depth, ways of interpreting the apocalypse, the numeric value of

ancient alphabets (gematria), the

relationship of apocalyptic thought to prophetic thought, and OT references in

the Apocalypse. I want to mention the OT reference appendix briefly because the

Apocalypse of John does not cite the OT at all, but it is generally accepted

that the text is drenched in the OT with over 800 allusions to various OT texts.

Fr. Donal supplies OT allusions, based on Ugo Vanni, SJ’s work in Italian, in

the hundreds, listing the possible OT allusions by chapter and verse in his

appendix. What a terrific aid and guide this is for any reader, beginning or

expert, for when John is read with the OT many “obscure” passages jump to life.

Fr. Donal also does

a terrific job of weighing the various means of interpreting this text, not

just in an appendix, but in his actual commentary. He gives proper weight to

the historical dimension of John’s text, accurately interpreting it in the

context of 1st century Rome, but he does not ignore the future

dimension of apocalyptic thought (the whole text, as he stresses, is about the

risen Lord and the return of the Lord sometime in the future) or the current

dimension (Jesus is Lord now and much of the Revelation of John has liturgical

context and liturgical meaning). The whole book is a sober examination, by an

expert, of a fascinating book, but “sober” should not be interpreted as “boring.”

Fr. Donal rescues Revelation from its wilder interpretations, or from those who

would sideline it as too strange or odd, and restores it to its rightful place

in the canon because of his focus on the Risen Lord at the center of his study.

I recommend this

little book, and I will be writing more on the apocalypse in the weeks ahead,

and encourage you to find a copy. I will even try to help you with that

process. I will continue to encourage Fr. Donal to find a publisher that can

distribute the book more widely – perhaps even an e-book would be a good means

to get wide circulation quickly - but in the meantime he says, “as regards

getting copies, I have plenty here in Fiji and am happy to ship them to people

who are interested.” I have not yet

asked him if I can supply you with his e-mail, but if he says yes, you will

find it in an update to this post. In the meantime, he does indeed teach at

Pacific Regional Seminary in Fiji!

Update: Fr. Donal is happy to have you contact him via e-mail if you would like to purchase a book: dmcilraithssc@hotmail.com.

John W. Martens

I encourage you to “Like” Biblejunkies on Facebook.