I am just starting my lectures on the origin and purpose

of the "five books of Moses" and my first-year graduate students are

getting excited about reading the Pentateuchal texts. Before that though they

need to be introduced to the origins and purpose of the Torah and I am sure

there would be a lot of questions. Here is a brief exposition on what I plan to

cover in the first few classes.

The first five books of the Hebrew Scriptures are known

as the Pentateuch (Gk. πἐντε [pente= five]; τεῦχος [teuchos = case]). These books are essentially arranged in the form of a narrative that

begins with the creation of the world and finishes with the death of Moses,

right before the people of Israel make their entry into the Promised Land.

Although these books contain a great amount of legislature and regulations, in

actual fact they are not books of law.

The first five books of the Hebrew Scriptures are known

as the Pentateuch (Gk. πἐντε [pente= five]; τεῦχος [teuchos = case]). These books are essentially arranged in the form of a narrative that

begins with the creation of the world and finishes with the death of Moses,

right before the people of Israel make their entry into the Promised Land.

Although these books contain a great amount of legislature and regulations, in

actual fact they are not books of law.

The Hebrew term תוֹרָה (Torah), by which the

Pentateuch is known, is most of the times conventionally translated as “law”,

but its meaning is better represented as “teaching”, “guidance” or

“instruction”. Therefore the Pentateuch does not present itself as a

comprehensive set of rules for life, nor does it develop a consistent

theological system, nor does it typically narrate the past to illustrate

obvious or explicit moral truths.

Although in most centuries the Pentateuch has been known

as “the five books of Moses”, perhaps because he is the major human figure in

the narrative, it has long been acknowledged that he cannot have been the human

author, and that the Pentateuch is in fact anonymous. Some scholars believe that

within the Pentateuch itself, Moses could be attributed with the

authorship of relatively small portions of its contents: Exodus 21-23, the laws

known as the “Book of the Covenant”; Numbers 33, the itinerary of Israel in the

wilderness; Deuteronomy 5:6-21, the Ten Commandments. These sections are among

the elements generally considered most ancient by historical specialists. I

find this most interesting. Whether or not Moses can be called the author

in a literal sense of anything in the Pentateuch, it is not impossible to hold

that the work and teaching of a historical figure were the stimulus for the

formation of the Pentateuch.

The overwhelming tendency in biblical scholarship has

been to explain the origin of the Pentateuch as the outcome of a process of

compilation of various documents, or better now, traditions or sources from

different periods of Israelite history. According to the classical

Documentary Theory of the Pentateuch, formulated by Julius Wellhausen and

others in the nineteenth century, the oldest written source of the Pentateuch

was the document J (so called from its 'author', the Jawhist or Yawhist, who

used the name יהוה (Yahweh)

for God. This source dates from approximately the ninth century BCE.

The E document (from the Elohist, who employed the Hebrew term אֱלֹהִם (ʼĕlohīm) for God, would have originated during the eighth

century. Many scholars think that the J and E sources were combined

by an editor in the mid-seventh century. The book of Deuteronomy, a separate

source dating from 621 BCE was added to the JE material in the mid-six century.

The final major source, the Priestly work (P), was mingled to the earlier

sources about 400 BCE. With all of this, the Pentateuch as we know

it probably came into existence no earlier than the end of the fifth

century BCE. Nothing that I have mentioned here concerning this

process remains unchallenged, and indeed the theory as a whole can no longer be

called the consensus view. It has become clearer with time that the written

documents' proposition is not holding well anymore and that most scholars

prefer now to talk more about the JEDP work as sources or traditions;

nevertheless, no other theory has gained any wide support.

At this point, the question would be: what is the

organizing principle of the Pentateuch as a whole, that is, considered as a

literary entity? An initial answer is obviously that the subject matter of the

Pentateuch is sufficiently unified to create the impression of general

coherence in the work. The last four books, beginning with the birth of Moses

and ending with his death, have a strong narrative connection. However, as I

agree with the vast majority of scholars, it is not accurate to regard the

Pentateuch as primarily a 'biography of Moses', for then there would be no

evident connection between these last four books and Genesis, for this book is

a narrative of the ancestors of Israel in general and not especially of Moses’

forebears.

Some authors have suggested that certain brief summaries

of the Pentateuchal narrative found in Deut. 26:5-10 and 6:20-24, indicate the

fundamental story line of the Pentateuch as a whole. These texts seem to have

the character of Israelite confessions of faith in the God who had directed

their history. These essential elements expressed in these passages express

certain “profession of faith” which corresponds (although roughly) with the

content of the Pentateuch. However, the events at Sinai are remarkably omitted

and anyone would acknowledge they are considered a major section in the Pentateuchal

narrative. Therefore, we would need a more conceptually unified theme in the

Pentateuch than a simple summary of its narrative.

I agree with many scholars’ opinion that the mainspring

of the action in the Pentateuch seems to be the divine promises mentioned in

Genesis 12:1-3 (that are repeated with various emphases in 15:4-5, 13-16,

18-21; 17:4-8; 22:16-18; which also are alluded in some other passages

throughout the Pentateuch). This promise contains three elements: a posterity

(“I will make you a great nation” v.2a) a relationship (“I will bless you”

v.2b) and a gift of land (“the land I will show you” v. 1b). In this

fulfillment and the partial non fulfillment of these promises we can see the

theme that would permeate the whole narrative of the Pentateuch.

|

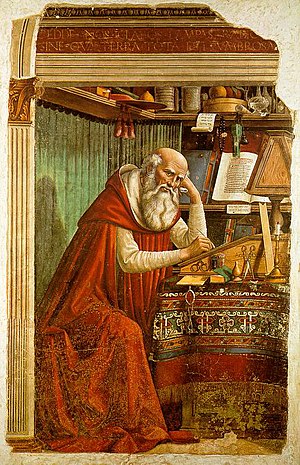

The Synagogue in Amsterdam

(Photo credit: photoikon.com) |

The theme of the posterity is is the evident motif of the

Book of Genesis. We can see in the Abraham cycle of stories the significance of

the many Genesis narratives of threats to the family survival: the sterility of

matriarchs (11:30; 25:21; 29:31), the strife between brothers (often with

near-fatal consequences, 4:8; 21:8-19; 25:23, 26; 27:42-45; 37:11, 23-24, 36),

and the repeated famines and difficulties in the land of promise (3:17-19;

12:10; 26:1; 42:5).

The theme of divine-human relationship is expressed most

strongly in the Books of Exodus and Leviticus. The events of the Exodus (10-15)

and the theophany at Mount Sinai (19) explain what the words of the promise (“I

will bless you”, “I will make may covenant between me and you”, “I will be your

God”) meant. The blessing comes in the form of salvation from Egypt and the

gift of the Law. The covenant of Sinai, of which the opening words are “I am

YHWH your God” (20:1) formalize the relationship foreshadowed by the covenant

with the forebears. The Book of Leviticus describes how the relationship now

established by YHWH is to be maintained. Therefore the sacrificial system is to

exist, not as a human means of access to God, but as the divinely ordered

method to repair and atone for failures in keeping the covenant. Finally, the

theme of the land dominates the books of Numbers and Deuteronomy. Numbers

begins with preparations for the conquest of the land, and ends with the actual

occupation of that part at the east of the Jordan by two and a half tribes.

Deuteronomy sets before the people laws for their life under God, explicitly

“in the land which YHWH, God of our fathers, is giving to you” (Deut. 4:1).

Now, none of the promises is fully realized

within the narrative of the Pentateuch itself. The posterity as ‘numerous as

the sand on the seashore’ is a promise that has only begun to see its

realization by the time the Pentateuch is over. The relationship of blessing

and of covenant is a continuing and never completely fulfilled promise, and the

land, at the end of the narrative of the Pentateuch is a promise that is

partially fulfilled. The whole structure of the Pentateuch, therefore,

seems to be shaped by the promises to Abraham, which are never final but always

point beyond themselves to a future yet to be realized. Although this opinion I

share with others is also susceptible to challenge, since I acknowledge that

there are several more ways where we can find some cohesion within the

Pentateuch, (as many as Theology of the OT textbooks present) so far this is

the one that makes more sense to me.

These considerations should serve as a basic

review or reading guideline when non-experts approach the Pentateuch writings. Our hope is to make their study more fruitful and

appealing.